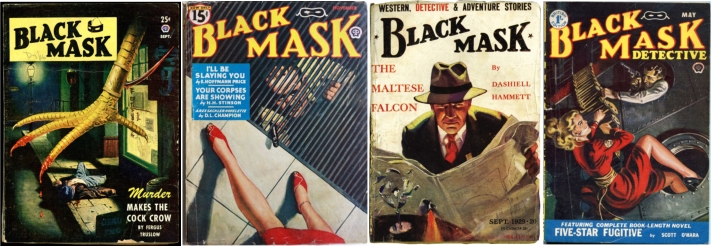

Chandler's stories are

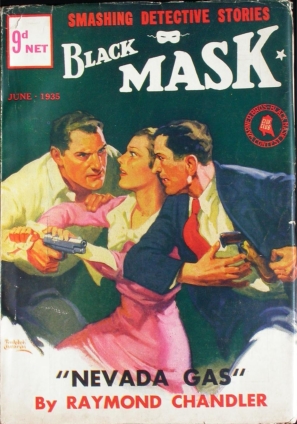

all episodic -- could be seven scenes (or Chapters) like The Red Wind (1938) or

twelve like Nevada Gas (1935), an evil tale about an evil gangster who has a

big saloon where the back seat can sealed off as a gas chamber. No one forgives

anybody in this one except the P.I. DeRuse, a gambler with a Mauser in an ankle

holder. His chick cheats on him with a double-crossing nightclub hood called

Dial but hey, all's fair in love and war, and Dial gets gunned anyway. The

central motif of the gas limo works as an ironic play on the State of Nevada's

means of capital punishment, i.e. death by cyanide gas. Hoods gassing hoods

seems fitting. Chandler was against capital punishment in general -- especially

for women -- although, as his stories show, some people deserve to die because

of their crimes.

The King in Yellow

(1938) is nine scenes about a hotel security man and his run-in with a jazz

musician who dresses in yellow and parties with his groupies until he implodes.

The title is a lift from the Robert W. Chambers (1895) 'The King in Yellow', a

play that drives all who read it mad. When Steve Grayce, the house dick finds

King Leopardi lying dead in faux yellow silk pyjamas, he says, "The King in

Yellow. I read a book with that title once...." It's unlikely that Leopardi

read it, though, so there's no real internal metaphor at work here, just a

motif, not an opera. Leopardi -- the familiar Faustian artist, beautiful music,

ugly personality. Murdered, of course. Live like a king, die like a bug.

There's a "plot" behind it all, although it's messy, like most of these Black

Mask stories. Chandler admitted he was "fundamentally uninterested in plot",

blamed himself for not planing far enough ahead when writing. To some extent it

was a problem of having too many murders in too short a distance, which then

leaves the finale expected, regardless of how unexpected the unmasking might

be.

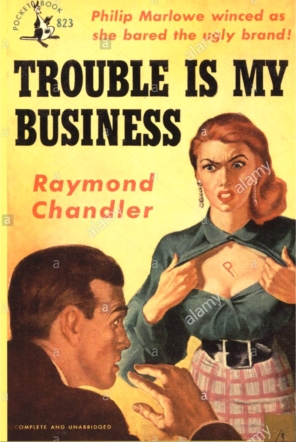

These 'mini-novels' --

collected under various titles such as The Simple Art of Murder or Trouble Is

My Business -- suffer from a density of violence that's less of a problem in

the long narratives, the Marlowe novels, starting with The Big Sleep (1939) and

ending with The Long Goodbye (1953) (or, if you prefer, the unfinished novel

Poodle Springs that Chandler was working on up until his death in 1959). In

fact, as has been noted by others, certain scenes and characters from the Black

Mask stories were used again in the novels, most obviously Killer In The Rain,

which provided a large and important part of the plot in The Big Sleep. The

names were changed, details here and there, but essentially Killer In The Rain

becomes the Carmen Sternwood smut photo blackmail gambit -- same rich girl,

same bookshop sleaze, same love-struck chauffeur, same blackmailers in the

wings.

'the love story and

the detective story cannot exist, not only in the same book -- one might almost

say in the same culture' (Chandler)

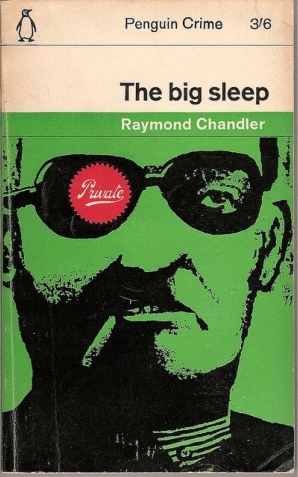

Is the Big Sleep

really Chandler's first masterpiece... or even a masterpiece at all? The

subject has been distorted by the Bogart-Bacall myth, and the rendering of the

movie version as a bad boy-bad girl romance. The ending of the novel is

jettisoned, the females airbrushed, and goodness prevails. This is not to say

that Bogart doesn't do a good job as Marlowe -- as Chandler himself said, all

Bogart had to do was enter a room to dominate a scene -- and that Bacall isn't

good in her role as an accomplished flirt and late night gambler. They are

good, but the script they follow is less about the grim story of moral

corruption presented in the novel than a Hollywood fantasy finessed for a

soft-hearted public. The look and the feel of the film is great, as you would

expect from an accomplished director like Howard Hawks, so it might be a bit of

a surprise to learn that it was scripted by the illustrious William Faulkner

and a young Leigh Brackett ('Queen of the Space Opera'). Of course the

narrative had to be abridged to fit the rhythm of a two hour movie and the era

was more comfortable with a male villain (Eddie Mars) than a killer slut

(Carmen Sternwood). Interestingly, Chandler thought Martha Vickers as Carmen

stole the female lead from Bacall as Vivian, but as the majority of her scenes

were cut in the final edit, her outstanding performance went by the

board.

'I came out at the

fourth floor sniffing for air. The hallway had the same dirty spittoon and

frayed mat, the same mustard walls, the same memories of low tide'

The novel made no

impact at all when first published, and it was only later when it was issued as

a paperback that it gained traction. The critics ignored it -- Chandler was

from the crime fiction ghetto. The opening, where Marlowe goes to the Sternwood

estate to receive his instructions is very good (and is one sequence the film '

faithfully followed) and the ending in the derelict oil field is likewise good.

This ending has a Gothic feel to it, re-jigged for the modern era of industrial

wealth and its consequence. The character of Carmen -- about as likeable as

Lucretia Borgia -- contains a secret within a secret, is actually driving the

action even when she isn't around. Marlowe, hired to solve one problem,

actually exposes a worse one more or less inadvertently because of his

fascination with big sister Vivian. Carmen's erotic photos and Vivian's

gambling are racy occupations in racy times, but aren't the real issue. It's a

clever plot, acted out in the noir shades of wind, fog and rain. Thunder too.

Perhaps the middle stanza is padded out a bit too much with story recaps --

i.e. when Marlowe visits the Bureau of Missing Persons -- which slow the

action, might cause a few readers to skip on (or drop out altogether). But the

narrative circularity is impressive.

'Knights had no

meaning in this game. It wasn't a game for knights.'

While you couldn't

call it supernatural, the resolving action has a strange feel to it, as if

Marlowe has been searching for his own killer, not the missing husband of the

woman he almost loves. It's not a happy ending, not a Hollywood ending, but it

is Hollywood and it is an ending.

'In Hollywood, they

destroy the link between the writer and his subconscious' (Chandler...

after he'd had enough)

Chandler made the big

time in 1944 when Paramount Pictures phoned and asked him to write the script

for Billy Wilder's production of the James M. Cain novel Double Indemnity.

Chandler worked with Wilder on vamping Cain's photo-dialogue, making it more

aural (rather than visual) to suit the L.A. vernacular. In a letter to Cain,

Chandler explained why he did what he did; it's a polite letter, although it

probably rankled Cain to be versed in the methods of the Hollywood screen

writer. It was a successful production led by three A-list actors: Fred

McMurray, Barbara Stanwyck, and Edward G. Robinson. Today Double Indemnity is

seen as the Holy Grail of the Hollywood film noir. In hind-sight, you can see a

lot of Philip Marlowe in the love chump insurance salesman Walter Neff, and his

sexual manipulation into committing a murder on behalf of the femme fatale

Phyllis Dietrichson. With a different ending, you could see Neff as Marlowe

before Marlowe becomes a shamus.

Due to the success of

Double Indemnity, Chandler soon got other gigs as a screenwriter, and why not?

He was a natural "scenic" writer, with or without dialogue. And his dialogue

was superb move-the-action-without-exposition stuff. He knew underworld jargon,

he knew business speak, he knew cop talk, he knew all manner of men and unlike

many male writers, he knew women well enough that women believed his female

characters. And he knew violence, could choreograph it like a drill sergeant.

But like most fiction

writers, he had trouble with the studio system, and the contractual requirement

that he be on the lot, in the office to be on hand for the director or the

producer or whoever needed him. Writers are by necessity loners. They don't

work well on the assembly line. Chandler had disagreements with Wilder,

insisted on working from home. He had the same problems with Alfred Hitchcock,

whom he didn't respect at all, called him "a fat bastard". The film they were

working on was Strangers On A Train (1949), from the novel by Patricia

Highsmith. Although the film remains popular today and is frequently cited as

one of Hitchcock's best, Chandler thought the plot was highly improbable, based

on a swap murder motif that would never happen in reality. Yet so much of the

basic mystery novel is based on game-play the public seemed to go along with it

all, despite this and a very flat ending. Chandler disliked Hitchcock's

penchant for placing visual effect before script, using unlikely angles (POV)

or weird shots through fishbowls and the like.

Chandler said:

"(Strangers) had no guts, no plausibility, no characters, no dialogue. But of

course it's Hitchcock....'

He had more control

over the situation with his script for The Blue Dahlia (1946), which was all

his, with a full ensemble of glittering night-life sleaze: a returning war

hero, a faithless wife, a nightclub hood, a blackmailing peeper, couple of

straightcops, a seedy skidrow hotel clerk, a brain-damaged vet, a fantasy

blonde and a whole lot of bodies on stage when all's said and done. The vet

(Alan Ladd) returns to L.A. with two buddies from the Pacific theatre to find

his wife Helen (Doris Dowling) in full party mode with her lover, a slick

operator who owns a nightclub called The Blue Dahlia. Eddie Harwood. Skinny,

with a skinny face and eye-brows for a moustache (the familiar dance hall

lizard). Things don't go well, naturally, and Johnny (Ladd) soon finds himself

on the lam for the murder of his slinky, hostile wife. However a mysterious

blonde in a coupe shows up and rescues Johnny from the rain, drives him to

Malibu in the first of a series of crude coincidences that has Ladd remark,

"Your timing's good...." Eventually nearly everyone is a suspect... some live,

some die... and a couple die very conveniently. Guess who: she's a tramp, he's

a hood. By the end it's she's a widow, he's a widower, and they might as well

get together, no tears lost. Chandler Lite.

The real Chandler has

a current of sadism running in his protagonists that few leading men caught.

Bogart did, Dick Powell was close, and Fred McMurray had a nice ambiguity about

him that fit his part. Chandler liked all three. He liked Alan Ladd, although

Ladd was just too nice, Boy Scout nice. Sure, his character knew a bit of HTH

(hand-to-hand) but he was too small, lacked that grit that the Chandler man has

when going up against the hoods. Gerald Mohr certainly had it (at least for

radio drama), a tough-love bully with a sense of humour and a sucker in the

clinch. Later versions of the Marlowe character are worth considering too. The

1983 HBO series starring Powers Booth is quite good. Mitchum tried but maybe he

was too old, too late, too Mitchum.

Chandler wrote a

Marlowe script that never made the screen but was later converted into the

novel Playback, published in 1958, just before his death. It's definitely out

of step with the earlier Marlowe stories -- romantic, more middle-class, sends

Marlowe to San Diego ('Dago') and the oceanside resort of Esmeralda in pursuit

of a fugitive babe, more or less in parallel with Chandler's own move to the

affluent suburb of La Jolla. It's another tale of blackmail, muggings and

sexual harassment. No doubt the SoCal location would've looked good in

Technicolor, but as a novel, you wouldn't want to rate it or date it as his

last.

Again, Chandler

Lite. |

The poetry of

illiteracy: Chandler started out as a poet in his younger days, published a few

poems in the London literary mags and papers of the day. His grasp of the

street idiom, its music, its rhythm, its metaphor, its attitude... the

sub-cultural politics, the anarchy and the telepathy. All this is brilliant.

Death comes in iambic pentameter, as it does for all poets. The hand gun was

the cell phone of the day, the fastest way of doing business. And the talk? The

talk was all poetry, street jive replete with subtext and code. Languages? Yes,

Chandler was good at languages. English, French, German... some Latin, some

Greek... and fluent street.

'The bell chimed

and a tall dark girl in jodpurs opened the door. Sexy was very faint praise for

her. The jodhpurs, like her hair, were coal black. She wore a white silk shirt

with a scarlet scarf loose around her throat. It was not as vivid as her mouth.

She held a long brown cigarette in a pair of tiny golden tweezers. The fingers

holding it were more than adequately jeweled. Her black hair was parted in the

middle and a line of scalp as white as snow went over the top of her head and

dropped out of sight behind. Two thick braids of her shining hair lay one on

each side of her slim brown neck. Each was tied with a small scarlet bow. But

it was a long time since she was a little girl.' (Miss Dolores Gonzales, Little

Sister)

His characters are

all first impressions, not recollections. Police aside, if he knows someone, he

knows him or her through the newspaper or the silver screen. Some are mere

rumours, although often show up under an alias. Even though Chandler used the

investigation narrative, for the most part what you see is what you get. L.A.

is a transient world. Everybody in Marlowe's reality seem to be from somewhere

else or nowhere at all. Some hoods might have a mythology but none ever have a

mother, and if they have a woman, well, she's strictly visual. And available.

And murder comes easily to just about any and all as if they're all combat

veterans and carry on as if the war has never ended, just spread to America,

became socialized.

"We're a big, rough,

rich, wild people," said Marlowe, "and crime is the price we pay for it." (The

Long Goodbye)

Johnny (Alan Ladd)

confronts his wife Helen (Doris Dowling) in The Blue Dahlia

'the best scenes I

ever wrote were practically monosyllabic' (Chandler) |