|

Of course, like

Gatsby, Stahr is a potential tragic figure because when you stand so high above

the crowd, you have a long way to fall if you stumble or if someone pushes...

or you decide to fall anyway, as the volition, the sensation, the romantic

madness that exists between hope and failure is preferable to the corroding

loneliness. Stahr is living on borrowed time anyway as he has a heart

condition, a weak spring in the clock. During a flood on the studio lot caused

by the L.A./Long Beach earthquake of 1933, he spots a woman who appears to be a

dead ringer for his deceased wife, the screen star Minna Davis. In the

confusion, the woman disappears, but Stahr soon tracks her down as he would a

potential starlet seen on the street or in a drugstore. It's a short, intense

romance. Kathleen Moore -- born in Ireland, educated in England -- is like

Cinderella after the divorce -- experienced, exciting, fatal. She belongs, it

seems, to another, leaves Stahr cruelly wounded and hitting the bottle. Cecelia

fills the vacancy and the story ends -- or at least ends as much of the story

as was written when it was interrupted by Fitzgerald's death from a heart

attack on December 21, 1940.

Oddly, there is a

narrative unity in the fragment that exists, like a long short story that

wanders on too far, engages too many satellite characters, yet seems to be

complete if romance is the only issue at stake. Kathleen Moore can be dismissed

to the supernatural, along with the 'old Monroe Stahr' (who was a sort of Ayn

Rand Superman, too lucky to be real), and Cecelia Brady gets her man, albeit

reduced by alcohol and a new found dissipation that makes him more human, more

real. The ellipsis leaves the future uncertain... but could it be any other way

for a hero with a terminal heart condition, never mind a ghost in the

closet?

Yet, it must be

admitted, the end is too sudden; there are too many scenes missing, too many

characters left waiting in the wings. And of course you know Fitzgerald's notes

sketched further scenes to come. As Edmund Wilson, the critic and friend of

Fitzgerald who edited Tycoon for publication says:

"(Fitzgerald) had

originally planned that the novel should be about 60,000 words long, but he had

written at the time of his death about 70,000 words without, as will be seen

from his outline, having told much more than half his story. He had calculated,

when he began, on leaving himself a margin of 10,000 words for cutting; but it

seems certain that the novel would have run longer than the proposed 60,000

words. The subject was here more complex than it had been in The Great

Gatsby—the picture of the Hollywood studios required more space for its

presentation than the background of the drinking life of Long Island; and the

characters needed more room for their development."

The story starts on an

airliner flying from New York to Los Angeles which is forced to set down in

Nashville for a few hours to sit out a storm coming up the Mississippi Valley.

Stahr is travelling under the alias 'Mr. Smith' with a couple of other studio

men, a writer called Wylie White and a Jewish producer called Mannie Schwartz,

although Stahr has the 'bridal suite' for himself at the front of the plane.

Cecelia is also on board, returning home for the summer after a semester at

Bennington College, an Ivy League school for the Arts where, she says, the

instructors fear and hate Hollywood instinctively. The modernity is exquisite,

not only because of the clean geometry of the writing, but because the setting

is on an airliner, an entirely new form of travel introduced to the public in

parallel with the talkies in the late twenties, as if its dreamy vernacular was

yet another Hollywood invention. The fact that Stahr flies in isolated luxury

in his own suite seems preposterous, because surely there were no aircraft in

the early thirties that would have a conceit such as a 'bridal suite'... the

detail is fantastic, like a Jules Verne invention, and you wonder if Fitzgerald

was just wandering into his Diamond Big as the Ritz mode, letting fantasy

sketch the politics... Hollywood mogul, lots of dough, carries on like Captain

Nemo.

Fitzgerald doesn't

name the aircraft model, although the writing is naturalistic and authentic.

The early workhorse aircraft for the transcontinental routes was the Ford

Trimotor, an elegant radial engine machine that could carry nineteen

passengers, or twelve if their seating was convertible to sleeping bunks,

although this seems an unlikely candidate for Fitzgerald's scenario.

Quite possibly he was

thinking of a German airliner, the

Fokker F-32,

a four engine Art Deco leviathan that Western Air Express (later became TWA)

used for its luxury-minded clientele flying in and out of Glendale, California,

in the early thirties. This Fokker monoplane was designed for fantasy,

affording the passengers the illusion of flying in small rooms decorated with

art panels, lighting sconces, and cushioned davenports beside the curtained

windows. In the early 1930s it was a long flight from the east coast to the

west coast, as these aircraft usually had to land and refuel every 500 miles,

and avoided night flying as they navigated by following natural landmarks and

painted concrete arrows set into the landscape. And landing just to avoid bad

weather -- as happens in The Last Tycoon -- was common, and passengers often

had to spend time in hotels and/or take the train for some sections of the

journey.

However, the Nashville

stop isn't entirely at the service of realism, as Fitzgerald sets up the tease

romance between the ambitious writer Wylie White and the young adventuress

Cecelia Brady by having them hire a taxi and visit The Hermitage, the home of

America's 10th President, Andrew Jackson, where they sit on the steps and await

the dawn, talk about Hollywood and flirt. There seems to be no reason for The

Hermitage scene other than the fact that Mannie Schwartz, who accompanies the

couple as a "chaperone" decides he's abandoning the journey back to Hollywood,

although the reason isn't immediately clear. He writes a note, gives it to

Wylie to pass along to 'Mr. Smith'. When they reboard the plane, Cecelia

realizes 'Mr. Smith' is in fact Monroe Stahr, an associate of her father,

someone she has known since childhood, a man 15 years her senior, an easy

romantic fixation for the young and restless Bennington junior. As for Schwartz

-- himself once the CEO of a movie combine "like United Artists" -- it seems

he's lost favour with Stahr, the boss of bosses, and has decided to drop out

entirely. Just what the reason is remains in the political shadow of the

culture that Stahr casts; you might not think of it at the time, but perhaps

it's an omen, a signal of things to come. While Schwartz carries an air of

quiet defeat and resignation, you're not sure what his direction will be --

suicide or revenge or the gutter or resurrection. Within the story fragment

that exists, the true meaning and function of this character remains moot,

although his cautionary note to Stahr perhaps says it all:

Dear Monroe, You

are the best of them all. I have always admired your mentality so when you turn

against me I know it's no use! I must be no good and am not going to continue

the journey let me warn you once again look out! I know. Your friend MANNIE'

In the 1977 Elia Kazan

film version the ending is written as an act of treachery when Pat Brady

(Robert Mitchum) calls a board meeting and has Stahr (Robert de Niro) removed

from power, advised to "take a vacation". There is due cause for this -- Stahr

got drunk and punched the 'communist' union leader Brimmer (Jack Nicholson)

when they failed to come to an agreement about the rights of some studio

members of The Screenwriters' Guild. While Stahr got the worst of the fight, it

was witnessed by Brady who uses the incident as an opportunity to displace his

partner and stymie the budding romance with his daughter Cecelia. While Stahr's

case of hubris might have its own rationale for this studio putsch, the

political subtleties are just too subtle as filmed. Despite its A-list cast --

Robert de Niro, Theresa Russell, Ray Milland, Jeanne Moreau, Jack Nicholson,

Dana Andrews, Donald Pleasance, John Carradine, Anjelica Huston -- and a script

by the premier stage dramatist of the day, Harold Pinter, the film fails to

capture Fitzgerald's cultural insight and story mysticism.

It doesn't help that

Kazan and Pinter skipped the plane (Chapter 1) entirely, opted to start their

story right on the studio lot, working up a montage from the screening room and

the soundstage, thereby ditching Fitzgerald's perfectly good set-up that

introduces the hero obliquely through the eyes of Cecelia Brady and uses the

metaphor of flight to romanticize the Hollywood 'high-flyer' set. The visual

possibilities of this period in American history when airline travel was still

a novelty were, for some reason, ignored. Either Kazan or Pinter were too

stage-locked in their thinking or there was a budgetary constraint that led to

this aesthetic blunder. It certainly helped kill the magic. While the (not so)

secret world of the studio film set with the actors and technicians doing their

thing has some appeal to the curious public, it all makes for a messy immersion

into the world of Monroe Stahr which is just the back story to his romance. A

cameo by Jeanne Moreau playing the diva during a film shoot does not replace

the plot function of the ingenue Cecelia Brady, the hopeful writer Wylie White,

the condemned producer Mannie Schwartz, and the man with the gold nugget ring

with the embossed letter 'S' (as if he was Superman) who reads scripts in the

plane's bridal suite and sits with the pilots in the cockpit:

'Stahr sat up front

all afternoon. While we slid off the endless desert and over the table lands,

dyed with many colors like the white sands we dyed with colors when I was a

child. Then in the late afternoon, the peaks themselves -- the Mountains of the

Frozen Saw -- slid under our propellers and we were close to

home.

'When I wasn't

dozing I was thinking that I wanted to marry Stahr, that I wanted to make him

love me....'

Beautiful, correct?

And these are not words for words' sake. Fitzgerald was writing at his modern

best -- straight clean lines that leave space for the imagination while driving

the action. If you've read any of the Pat Hobby stories -- the Hollywood series

that was published monthly in Esquire between January 1940 and May 1941 thereby

spanning Fitzgerald's last days and death -- you will experience this economy

of form at its most sublime. There's an urgency to the writing, where the story

and only the story matters, as if delivered between drinks in some Hollywood

bar. Obviously there's a 'pictorial' influence, a screenwriter's sense of

scene, an oral sense of brevity rather than pretty verbal exposition. As an

expose of life on the studio lot in the 1930s there is nothing to match these

stories. As a 'writer', Hobby is a Falstaffian hustler who was 'big' in the

silent era, and now struggles to get any screen credits at all in the talkies.

Forty-nine years old and living from fantasy to fantasy -- often ripped off

from some other wannabe sucker -- he lurches around the studio lot like a bit

player from the silents trying to keep up to the relentless future. In fact, in

one story he blunders into the middle of a live scene while trying to graft a

loan from a producer and is then forced to wear a iron stunt vest and allow

himself to be driven over by the star. Desperate for money, he agrees but the

scene goes awry and he's left in a ditch all night trapped by his iron vest

until rescued by a studio cop at dawn.

Many screenwriters no

doubt felt as if they were wearing an iron straight jacket as they laboured

cruelly, tricked by easy promises and their own desperate optimism. Fitzgerald

was definitely writing under such pressure in the three years before his death,

recovering from his 'Crack-Up' period, struggling to find the cash to pay for

his wife's medical quarantine, their daughter's school, and whatever it takes

to pay for food and lodging. It was a tough life for writers; even exalted

figures like William Faulkner and Aldous Huxley, lured to Hollywood by the

prospect of big money, struggled to pay for the groceries.

Pat was forty-nine.

He was a writer but he had never written much, nor even read all the

'originals' he worked from, because it made his head bang to read much. But the

good old silent days you got somebody's plot and a smart secretary and gulped

benzedrine 'structure' at her six or eight hours every week. The Director took

care of the gags. After talkies came he always teamed up with some man who

wrote dialogue. Some young man who liked to work.

"I've got a list of

credits second to none," he told Jack Berners. "All I need is an idea and to

work with somebody who isn't all wet."

(A Man In The Way,

pub. in Esquire, February 1940)

Here, it's as if

Fitzgerald was reconnoitering his own fade-to-black as he too passed into

middle age, found himself writing scripts that never made the screen, or if

they did, someone else's name was on the credits. His books were out of print,

he was alcoholic, his wife in the madhouse, and he was living like a nomad. Pat

Hobby is by no means a self-portrait by Fitzgerald -- he's uneducated, doesn't

read if he can help it, never stayed married more than a month or two --

although he's a barometer of sorts. Where the examination of Hollywood studio

culture is almost naturalistic in Tycoon, in Pat Hobby the gestalt is a

full-throttle uninhibited expose. To be sure, it's often burlesque, an

absurdity that could be easy fiction, yet the authenticity is beyond any

thespian fraud dreamed up by a screenwriter with a grudge. The economy of form

in these stories approaches minimalist perfection. Although they were probably

written in haste 'for the money', their pictorial narratives move with the

montage speed of a superbly edited series of film shorts on a common

theme.

'I saw that the

novel was becoming subordinated to a mechanical and communal art that whether

in the hands of Hollywood merchants or Russian idealists, was capable of

reflecting only the tritest of thoughts, the most obvious emotion.'

(Fitzgerald, The Crack-Up)

Fitzgerald outlined a

possible 31 chapters or scenes for Tycoon, and only completed 17 before his

death. He imagined Stahr going for revenge against Brady, hiring an assassin to

take him out, then having second thoughts; yet before he can decommission the

hit, is killed in a plane crash in Oklahoma while en route to New York. The

appeal of this plot is in the circularity, the looping of Chapter one as the

shape of fate, and its deadly irony when considered against Stahr's cocksure

judgment.

Some say Fitzgerald

was a nasty piece of work, and seems to have had a habit of using women as

characters first and lovers second. On his first attempt at Hollywood in the

late twenties, he had an affair with the starlet Lois Moran who later ended up

as the template for Rosemary Hoyt in Tender is the Night (1934). Of course,

there's nothing unusual in this -- writers use people they know either

consciously or unconsciously all the time for their characters -- and whether

or not there is/was some moral treachery involved here is a matter of opinion

and political memory.

Kathleen Moore =

Sheilah Graham

'Stahr did not

answer. Smiling faintly at him from not four feet away was the face of his dead

wife, identical even to the expression. Across four feet of moonlight the eyes

he knew looked back at him....'

A supernatural

event... or just a desperate widower's needy hallucination? Stahr doesn't seem

to be particularly desperate, although the minions who serve him might be. The

lack of information about his deceased wife contributes to the feeling that

this is a man who doesn't look back, who just keeps moving confidently into the

future at 24 frames per second. Yet, as we come to learn, he is a lonely man,

one who never allows his name to appear in the credits of the many films he

produces.

Stahr's romance has a

mythical sense about it, as if Fitzgerald was not only writing about himself

and Sheliah Graham, but also about that sort of Orphic love whereby the dead

lover returns from the underworld simply to draw the bereaved to the other

side. As femme fatales go, Kathleen Moore is a beautiful consolation prize

hijacked by Minna Davis for one last dance in the moonlight before Stahr's own

inevitable departure. His partially constructed beach house where he romances

Kathleen is merely an ante-chamber between sex and death, the incomplete

'present' which can only be measured by the distance between first and last

love, now one and the same. It's possible that Stahr is suffering from movie

hypnosis, whereby his aesthetic ideal is bound to come back at him in an ghost

studio that is forever inside his head. An earthquake delivered Kathleen to

him, as if the flood drew her from the underworld riding on the giant head of

Siva, and, while entirely natural in the course of events (there was an

earthquake in the Los Angeles area in 1933 that broke water mains and caused

buildings to collapse), the incident paints itself in symbolism.

Although the giant

head is detritus from a jungle set, some might think the Hindu god 'Shiva'

was/is misspelled deliberately as 'Siva' in order to suggest the Jewish ritual

of consolation for the bereaved. The ambiguity is interesting, as the Hindu

Shiva is the god of destruction (in order to make way for a new cycle of

creation), and certainly fits well with the minor disaster that has struck the

studio lot. Yet the Siva head is just a film prop, another Hollywood fiction

that serves the dream factory. So when Stahr saves his dead wife's incarnation

from the flood, perhaps he's become a victim of the fantasy he has staged so

often for the public. You can read too much into the background architecture of

Fitzgerald's narrative, of course, although incidents such as this trigger

associations.

Fitzgerald obviously

based Kathleen's character on his last paramour, Sheilah Graham, the well-known

Hollywood gossip columnist who emigrated from England in 1933, ditching an

older, paternalist husband and a gig as a chorus girl in London's West End. It

was a hot romance, a sweet mix of body beautiful and elegant words, but of

course volatile as Fitzgerald was vibrating between addiction and poverty, and

Graham was carrying secrets that only love could unlock:

As she put it in

her book College of One (1966), during his great drinking binge of 1939, he

screamed “all the secrets of [her] humble beginnings” to the nurse

taking care of him. That same day, my mother and Fitzgerald grappled over his

gun, and she made the pronouncement of which I think she was rather proud,

“Take it and shoot yourself, you son of a bitch. I didn't pull myself out

of the gutter to waste my life on a drunk like you.” What Fitzgerald had

screamed to the nurse, my mother eventually told me, though she never brought

herself to write it in any of her books, was that she was a Jew. (Robert Westbrook, novelist & son

of Sheilah Graham)

Fitzgerald himself was

like Bronte's Rochester, a tortured man dealing with the demons that come with

having an insane wife locked up in a private asylum and so you would expect

this part of his unhappiness to migrate into the character of Stahr. You learn

that Stahr's wife is dead some three years earlier, the circumstances left

untold within the narrative that exists. She was a movie star called Minna

Davis and while Stahr doesn't seem to suffer much from the memory -- he's too

busy with running a big movie studio to be distracted by death, it seems -- yet

his loneliness is a subtle disease, as if the memory of his dead wife is locked

in his head like a ghost, and is manifested in his hunt for Kathleen Moore,

which seems at first to be just an imprudent detour from the business at hand.

As his character is revealed through action rather than exposition, and his

interest in this unknown trespasser on the studio lot could well be nothing

more than a movie man's business intuition that this babe would look good on

the screen, Stahr's motive is ambiguous at first... and perhaps he doesn't know

his reasons himself beyond the fact that this woman is a dead ringer for Minna

Davis.

There's a faint

Jamesian ghost story motif at work here, and although the modernism keeps the

supernatural distant, it's keen enough to drive a sense of romantic tragedy in

the making.

There were two

revolutions at the close of the twenties -- the stock market crash and the

advent of the "talkies' -- and both figure heavily in the cultural turmoil that

landscapes the action in The Last Tycoon. The lack of spending money affected

box office intakes and the talkies affected the entire movie production

routine. Before, it was "tell the story in pictures" but in the thirties the

pictures had to coexist with dialogue, so there was a large influx of

professional writers, hopeful journalists and elite novelists and playwrights

like Aldous Huxley and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Unlike Huxley, Fitzgerald grasped

the format requirements quickly, as his Pat Hobby stories about a hustling

screenwriter reveal, and the pared down modernist narrative style that came out

of films is in full force in The Last Tycoon. The 'Conference' session scenes

that Stahr conducts with his producers and writers are a true insider's view of

the process. Producers struggle to find 'the story' and stay on budget while

writers struggle to write in scenes and be pictorial before being verbal... but

verbal nonetheless.

The pictorial method

came out of 'the silents' and in a sense film never left it as an aesthetic

anchor. Even in action films today dialogue is mere noise, a dumbed down lyric

that's just part of the soundtrack where emotion is best served by an atonal

melody. How different is this from yesterday's orchestra or lone pianist

emoting from the twilight below the screen? Still, the close up with a

supporting monologue was now part of the drama, and the verbal skills of the

theatre dramatist were in demand. The 'talkies' introduced an intellectual

level and intellectuals were brought in to work in 'pairs' -- usually a man

with a woman to get both sides of the dialogue, or a neophyte with an

established pro -- even if oftentimes their efforts went unread or if used,

their names never appeared in the credits. In The Last Tycoon, Stahr has a

chain of 'pairs' writing on the same story, each a backup or alternative to the

pair in front. Usually these pairs worked in ignorance of one another, although

not naive to the possibility. This assembly line method of writing pairs was an

innovation attributed to Irving Thalberg, the famous boy wonder producer at

MGM, who died aged 37 in 1936 of heart failure, and is still considered by many

commentators and Hollywood historians to be the greatest figure ever in the

economic evolution and aesthetic shaping of the film industry.

So it's no surprise

that most people think Fitzgerald's character Monroe Stahr was based mostly on

Irving Thalberg -- like Thalberg, Stahr was married to a movie star and

suffered from a congenital heart defect, and was known to already be living

beyond his years. Yet Stahr is also like Fitzgerald himself, blessed with early

success and the sense of invincibility that such success brings. And love -- O

tainted love -- which is both a reward and a future punishment, perhaps for

unwitting arrogance, or perhaps capricious fate. Fitzgerald loses Zelda to

madness, and Stahr loses Minna to early death... and then, like Fitzgerald,

Stahr suffers a "crack-up" when Kathleen chooses an old lover, leaves him in

the lurch. Stahr's emotional geography is something very familiar to the

writer, an autobiographical surrogate dressed in mythological possibility.

Perhaps because he

exists only in a narrative fragment, Stahr isn't particularly real or even

sympathetic as a character, especially when he appears in the 3rd person -- his

'close-up' -- and you get to see the private Stahr, the off-stage Stahr.

There's something insubstantial about him, as if he can only be seen in the

long view, through the eyes of others. He is most real when seen through

Cecelia's P.O.V. Love is blind, the saying goes, yet here love is clear.

"He was born

sleepless, without a talent or the desire for it," she says.

And later: "(Stahr)

was a marker in industry like Edison and Lumiere and Griffith and Chaplin. He

led pictures way up past the range and power of the theatre, reaching a sort of

golden age before the censorship in 1933."

Well, perhaps it's the

P.O.V. shift that dims the portrait, removes the light. Fitzgerald builds Stahr

as an idea, a quasi-Nietzschean superman, the sort of Promethean hero that Ayn

Rand developed in antipathy to communism and its sublimation of the individual.

Stahr is a master of the 'quick read', both of scenarios and people. And an

individualist.

Boxley =

Huxley?

Boxley, rhymes with

Huxley, so who knows, maybe Fitzgerald used Aldous Huxley for this character,

the English novelist whom Stahr has under contract, even though he doesn't know

how to write a film script. Huxley had the same problems and frustrations as

'Boxley' with both the studio system and trying to master the 'pictorial'

method of screenwriting. When he and his wife Maria first arrived in Hollywood

in 1937, they put up in the Garden of Allah, where both S.J. Perelman and

Fitzgerald were staying, so Fitzgerald would've seen first-hand Huxley's naive

entry into the motion picture industry.

Actually Stahr -- like

his real-life model, Irving Thalberg -- handles the frustrated novelist

diplomatically, and their encounter reveals his legendary 'long-view' way of

doing business. The Boxley name -- like Huxley -- has cachet, which the studio

can benefit from even if nothing he writes actually makes the screen. Besides,

as Stahr says, sooner or later he'll figure it out. This scene has a certain

authenticity to it, and while amusing, doesn't discredit Boxley/Huxley, and

illustrates Stahr's industrial approach to the art.

Another clue that

Boxley resembles Huxley is that Huxley worked on a screen play about Madame

Curie, which Fitzgerald later took over. What happened to Huxley's 145 page

attempt? According to Salka Viertel, the writer who eventually got the screen

credit, the producer gave it to his secretary to read, who proclaimed that "it

stank" and was therefore immediately forgotten.

In 1938 Huxley wrote a

novel called After Many a Summer Dies the Swan based on Randolph Hearst the

newspaper tycoon; it might have had some influence on Orson Welles and his

Hearst project, Citizen Kane, and likewise on Fitzgerald.

Fitzgerald has a

heart-felt line in The Crack-Up which describes both himself and Stahr: "The

ego would continue as an arrow shot from nothing to nothingness." The fatalism

here underscores the romanticism of both success and tragedy, and the paradox

of life and death. As it stands, there's no way of knowing if Fitzgerald's hero

is a winner or a loser within the human scale of such measurements. You suspect

that like his previous heroes, Stahr is a slave to beauty, the hidden muse

behind his art... albeit that his art is industrial art, a dark room seance for

the masses. The familiar Fitzgerald masochism is there, the need to suffer in

order to keep the flame alive. When Orpheus failed in his attempt to recover

Eurydice from the Underworld, he went homosexual, and as a consequence was

ripped to pieces by some jealous Thracian women... apparently. While Fitzgerald

didn't project this fate onto Stahr exactly, he was to be destroyed in an

aircrash, a counterpoint irony to the hit he ordered on Brady.

If you have a copy of

Tycoon that includes Fitzgerald's notes for the rest of the novel, you can

consider the work as a post-modern narrative that allows the reader to impose

his or her own preferences, decide the fate of the characters. Mannie Schwartz

commits suicide... Brady manipulates a film editor into killing Stahr...

Kathleen reappears as the film editor's lover... maybe the plane is

booby-trapped... maybe the wreckage is found by some teenagers who loot the

baggage, forget to tell the authorities about the bodies in the snow... maybe

there's a big Hollywood funeral... or maybe Stahr and Kathleen end up on a nice

warm beach before Pearl Harbor changes everything. Fitzgerald hadn't decided;

he was mulling options.

Perhaps one should

look at the ending of The Great Gatsby to see how it might've gone for Tycoon,

as writers repeat patterns, and Fitzgerald was no different. The summation

would come from Cecelia Brady, as she is the correlation to Nick Carraway, the

bedazzled neighbour who befriends Jay Gatsby and is the only mourner at his

funeral. Because the studio is run by a majority of Jewish businessmen, that

angle would be explored, just as it is in Gatsby when Carraway visits

Wolfsheim, Gatsby's business partner in a futile quest to get him to appear at

the funeral. Gatsby was shot in his swimming pool by mistake, although the

shooter thought it was no mistake, merely drew the wrong conclusion from the

right information; this sort of ironic justice would play out in The Last

Tycoon.

A roman à

clef masterpiece? Possibly. The Last Tycoon is certainly a historical

marker for all sorts of reasons beyond its importance within Fitzgerald's work.

But if this fragment -- this uncompleted novel -- was all that Fitzgerald had

ever written, would there be enough cultural gravity out there to keep it going

like, say, that other famous fragment, Coleridge's Kubla Khan?

© LR

September 2016

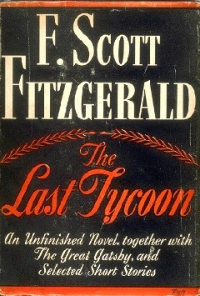

The Last Tycoon

at Amazon: US | Canada | UK

*Check out LR's

OUTLAW

ACADEMIC »»

or LR's novel

RADIO

BRAZIL »»

|