The Workings The subversion of linear narrative, along with naturalism and the consolations of genre, can be traced back over a hundred years and is perhaps typified by the pioneering surrealist text The Magnetic Fields (1920) by Andre Breton and Philippe Soupault, an experiment in ‘pure psychic automatism’. It is the exploration of a European urban dreamtime after the trauma of the First World War and the disruptive impact of non-linear electric media. ‘Prisoners of drops of water, we are but everlasting animals. We run about the noiseless towns and the enchanted posters no longer touch us.’ It could certainly be seen as an ancestral paradigm for Makin’s Work, which could also be related to the cut-up novels of William Burroughs, illuminated by flashing jump cuts: ‘ – cross wounded galaxies we intersect, poison of dead sun in your brain slowly fading – migrants of ape in gasoline crack of history...’ (The Ticket that Exploded, 1962) Yet Makin doesn’t use cut-ups, stating in an interview with publisher David Vichnar that he prefers to ‘employ a rigorous method of rearranging the text — a way of inviting chance and accident — which is essentially numerical, and could be described as a way of tripping oneself up, placing potentially productive obstacles on the path.’ In this context the work could be seen as a work-out, as a ritual magical working, the alchemical Great Work, even as the Work-on-Oneself in Gurdjieff’s sense, breaking down the habitual reflexes of everyday perception and language.

For this vast prose poem is a wild fugue of intertextuality and polyphonic entanglement, a mosaic of glittering narrative shards, an explosion of verbal shrapnel. ‘From the opening words: bitter roadkill, composite with tubular heads of yellow steel, a great aluminium star afloat on the ocean.’ The prose pans across landscapes of decay and monstrous rebirth, a manic teratology. We catch glimpses of sci-fi dystopias, cosmic (or comic) apocalypse, doomed marine voyages, war-zones ancient, mediaeval or modern. There are frequent close-ups on carnage and torture - ‘His tongue is branded with a red-hot iron before the firing squad takes aim.’ - juxtaposed with desperate pleasures. ‘Glad you enjoyed the ossuary fuck.’ So many asides contain the DNA for an entire novel. ‘One of the Norse gods then described how he once slew himself by swallowing the world’s ashes.’ Personae wrestle for their moment in the tracking spotlight of consciousness, from paragraph to paragraph, sentence to sentence, from one subordinate clause to another. ‘You’re not sure if you’re reading or being written.’ Each sentence seems suspended in its own zone of radiation, generating a drift of fall-out over the next. Locations in space/time shift rapidly, with only occasional hints of specific co-ordinate points. One is Zagreb. Makin lived there from 1987 to 1990 and continued to visit the former Yugoslavia during the wars of the 1990s. The other visitor experience that keeps recurring is a decaying coastal landscape, like the seaside town of St Leonards, (formerly a run-down enclave of displaced feral lunatics, now partially upscaled) where Makin has lived for some years. Yet this mutating POV is delivered in carefully structured paragraphs, with recurrent tropes and leit-motifs, in the manner of a Wagnerian operatic score. Like its predecessors, Dwelling (Reality Street 2011) and Mourning (Equus Press 2015), it consists of thirty-three chapters. As Makin explains, ‘All three books somehow exist for me at once, simultaneously, regardless of when the physical volumes appeared.’

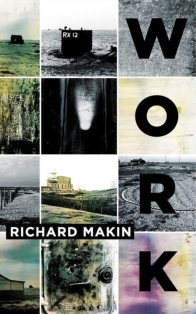

Makin was educated as a painter (BA Fine Art, post-grad Royal Academy) and delineates his surreal landscapes in with a precise painterly use of language. In places there could be comparisons with Dali, Magritte or even the giant vitrines of the Chapman Brothers, tableaux of nightmarish monstrosity. ‘He was more animal than human, flamboyant bill studded with minute sensors, robbed of which he would never dine. His internal organs are constellated in a delicate fan array. I entered the cell to find him lying on a heap of filthy straw...’ The vocabulary is enormous and the range of reference is encyclopaedic, embracing surgery, anatomy neuroscience, biology, botany, astronomy, physics, engineering, electronics. Neuroscience becomes the new Pataphysics. ‘A small translucent cover for intimidating indoor plants has been grown from a clump of brain cells.’ ‘There is a condition in which fluid accumulates in the brain, driving the volunteer on and on in a forced march across a frozen landscape...’

|